- 9th of June 2018

Interesting information

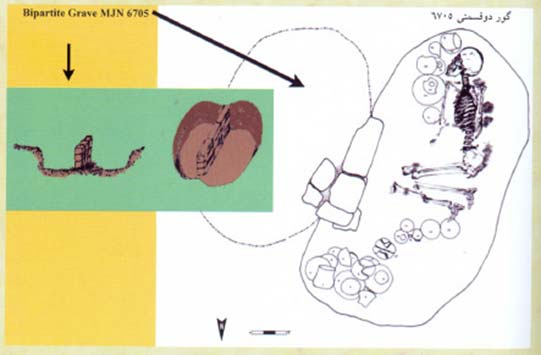

An artificial eyeball in the grave no. 6705:

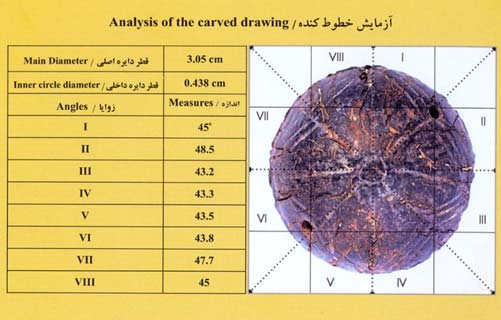

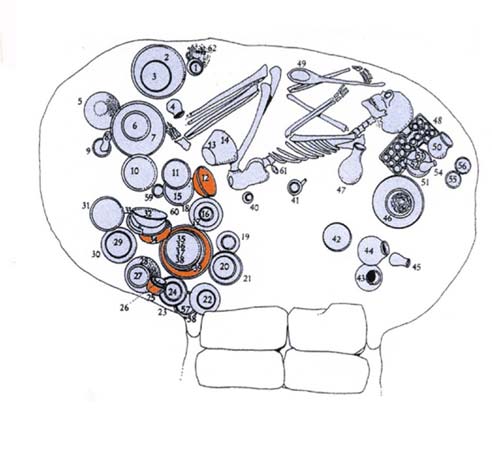

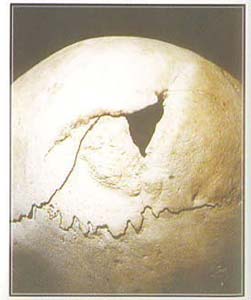

The earliest attestation of artificial eyes in the ancient Near East has long been believed to be represented by art eyes and artificial eyes found with mummies, sarcophagus lids and statues, dating back to the third–second millennia B.C. Recent excavations at Shahr i Sokhta, in the Iranian region of Sistan-Baluchistan, have produced new evidence that could question this view. The excavations carried out in square MJN revealed one grave (No. 6705) containing a well preserved skeleton of a young woman. The grave is 218 cm. long, 105 cm. wide and 152–66 cm. deep, the general shape is an oval, and structurally it is of bipartite type. The skeleton belongs to a female of about 28–32 years of age who had a hyper-dolicocefal skull, and who at about 180 cm. is the tallest woman ever found at Shahr-i Sokhta. A total of 30 objects were found in this grave, 25 pottery vessels, 1 copper/bronze mirror, 10 lapis lazuli or turquoise beads, 1 decayed mat basket and 1 small leather bag. From the remains of textile fragments attached to the bones, it seems that the skeleton was wrapped in fabric. Traces of burning are evident on the ankle of the skeleton in keeping with Shahr-i Sokhta’s burial customs. The skull appeared to be partially damaged on the left side and the cleaning revealed the presence of an artificial artefact inserted in the left eye socket. This artefact has a diameter of c. 3 mm. and is very well preserved (Fig. 11). It is made of a lightweight material, probably derived from bitumen and animal (pig?) paste. Its surface is meticulously engraved with a pattern consisting of a central circle for the iris and silver/gold rays departing from it. On the surface, very tiny traces of white colour are also visible. The golden/silver lines were applied in a very thin layer over the surface and they are still remarkably visible. On either side of the half-sphere, two tiny holes have been drilled, through which a fine thread was presumably tied to keep the artefact in place. Microscopic examinations of the skull found marks left on the eye socket by the prolonged contact with the artificial eye. The socket also bore the marks of the thread, further proving that the owner of the artificial eye wore it when alive as well as in death. In addition, a very preliminary analysis suggested that the woman may have suffered from an abscess on her eyelid because of long-term contact with the artificial eye-ball as an ocular prosthesis. Chronologically, this artificial eye ball could be dated to the Phase 9 of the occupation at Shahr-i Sokhta; i.e. 3000–2900 B.C.

The grave no. 6705 with artificial eye

The skull of female skeleton related to the grave no. 6705 with artificial eye

artificial eye

Leather bag that was used for keeping the artificial eye

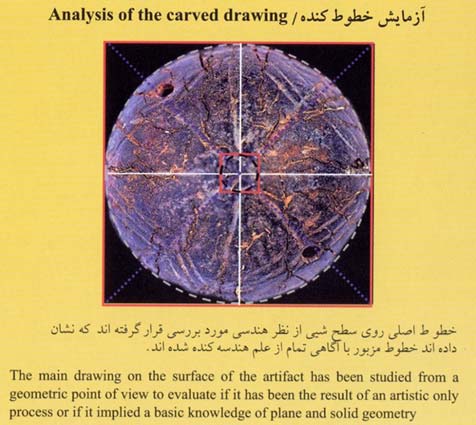

Analysis of the carved drawing

Analysis of the carved drawing

The oldest animation depict the goat eating the leafs

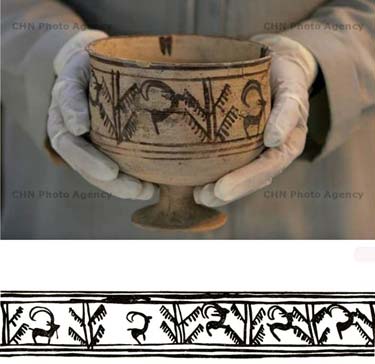

A 3rd millennium B.C (2800 B.C) brandy cup discovered in Shahr i Sokhta has five sequential images painted around it that seem to show phases of a goat leaping up to nip at a tree.

This cup found in Shahr i Sokhta in the 1970s features a series of five images that researchers have only recently identified as being sequential, much like those in a zoetrope. Giving the bowl a spin, one would see a goat leaping to snatch leaves from a tree, as seen in the video clip below.

The remarkable piece of pottery was unearthed from necropolis of Shahr i Sokhta by Italian archaeologists, who hadn’t noticed the special relationship between the images that adorned the circumference. That discovery was made years later by Iranian archaeologist Dr. Seyyed Mansur Seyyed Sadjadi, Iranian director of excavation at Shahr i Sokhta. It was originally thought to depict the goat eating from the Assyrian Tree of Life, but archaeologists now assert that it predates the Assyrian civilization by a thousand years. Iran’s Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts Organization (CHTHO) and director Mohsen Ramezani have created an 11-minute documentary on the discovery. A ceremony celebrating the film’s completion was held on Sunday in Iran.

Plan of the grave no. 731 with wooden game plate and a brandy cup with five sequential images painted around it that seem to show phases of a goat leaping up to nip at a tree.

Painted buff ware chalice with moving goat that is a first sample of animation in the world dated back to 2800 B.C (4800 years before present)

Brain operation in Shahr i Sokhta

During the archaeological excavation in Shahr i Sokhta in 1978, a skull of teenager belonging to 4800 years ago, was found in a mass grave. There is a deep triangle like a scar on the right side of the skull. The skull, 51 cm in circumference belonging to a girl aged 13 or 14 years old, was discovered in Shahr-e Sokhta, (3200 –2000 BC) dating back to 2800 BC. As anthropologists believes that the brain had been operated for Hydrocephalisis disease. The skull had been operated to bring waste material out of the brain. The girl had lived at least for six months after the operation, since a tiny bone, which had grown after the operation, can be seen near the cut.

The skull of teenage girl that had been operated for Hydrocephalisis disease

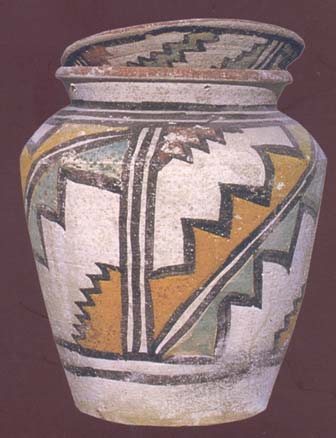

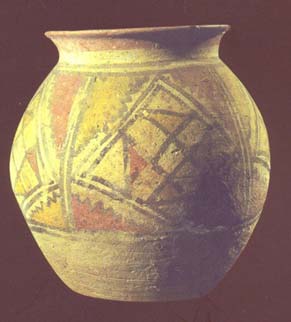

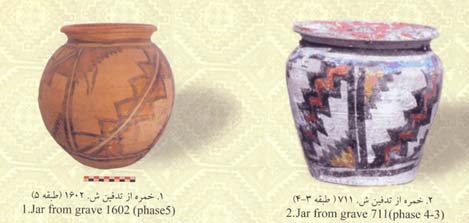

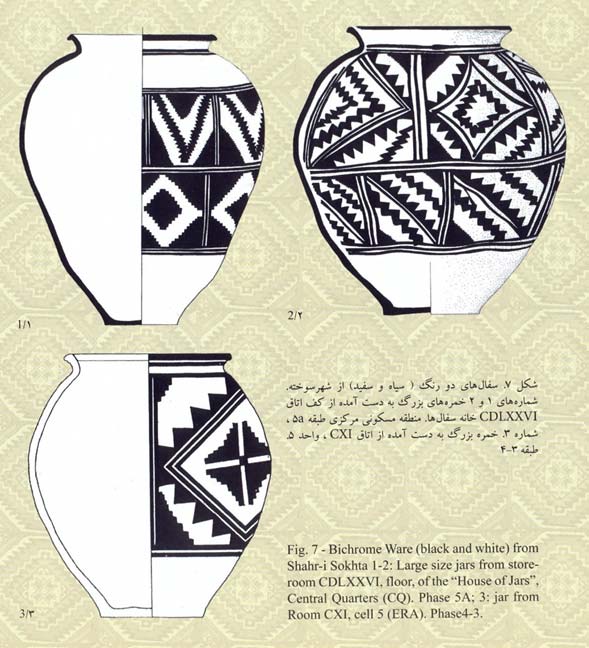

Polychrome wares

Polychrome wares, mainly found at Shahr-i Sokhta across the relative sequences of the 3rd millennium B.C. may be distinguished from more common wares by the post-firing painting in various colours and by a repetitive system of geometric patterns appearing on the shoulder and the maximum expansion of medium to large-sized restricted vessels. While the precise function of these peculiar vessels is still unknown, the aesthetics of the painted decoration recal1s the patterns of stamp seals, as a rule worn in graves by women, and the vessels themselves in the graveyard are preferentially associated with female individuals. We be1ieve that Polychrome jars were actual1y 'skeuomorphs' or ceramic replicas of large baskets or containers woven in vegetal fibers. Polychrome containers, as far as we know, were made at Shahr-i Sokhta in a dozen basic forms, including jars, pots and, more rarely, truncated cone-shaped bowls used as lids. The maximum formal variability was reached in Period II (c. 2750-2500 B.e.) in correspondence with the peak of formal and graphic elaboration of the more common Buff Ware products.

Polychrome ware from Shahr-i Sokhta

Polychrome hemispherical jar

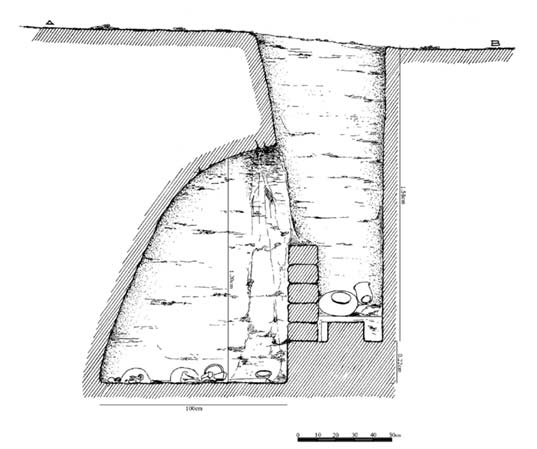

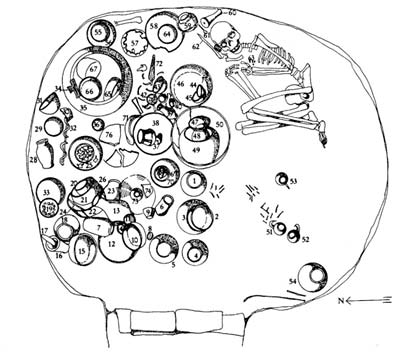

Catacomb Graves of Shahr-i Sokhta

This grave type has a vertical, rectangular shaped pit with various depth among different graves and an elliptical chamber that opens into one of the long sides of the vertical shaft connecting it to the underground chamber. The floor of the chamber is lower than the floor of the vertical shaft. After the inhumation the entrance of the underground chamber was closed by a mud brick wall, and the vertical shaft was filled up. This grave type was used for both individual and multiple burials. According to some researchers, this type of grave was mainly built for family groups, but further excavations and researches showed they might have had a different function to which we will come back later. While the passage connecting the shaft and chamber of pseudo-catacombs (type 3) is marked by one or two rows of mud bricks, the entrance doors of catacombs (type 4) are completely closed. It seems that this type of imposing grave could well belong to a distinguished class of society, as indicated by the grave structure, and the quality and quantity of grave goods.

The catacombs are composed of two distinguished sections: a vertical pit and an underground chamber. Here, bodies and grave goods remained for thousands of years without any direct contact with dirt, natural agents and other chemical materials, ensuring that the decomposition of the skeletons and the decay of the corruptible materials were very slow and thus, when dug, they were recovered in better conditions than what found in other grave types. Catacomb graves, very similar to those of Shahr-i Sokhta have been seen in Central Asia and ancient sites of southern Uzbekistan, in the valleys around Amu Darya and sites such as Sappally Tepe, Jarkutan and some other sites, all of the Bronze Age Period . Also, at least one of this type of grave has been reported as built by the Velikent culture in Caucuses, suggesting that the use of this kind of grave structures is not merely typical of Central Asia and Southeast of Iran.

The catacomb no.1705 during the excavation

Section of catacomb no.19

Plan of a catacomb grave. Grave no. 725

Catacomb grave goods. Upper: grave no.5005 and lower: grave no. 1615

The goods of catacomb grave no.9034. 1- Polychrome jar with cover 2- Clay/Metal incense burner 3- Cooper/Bronze mirror 4- Polychrome painted leather